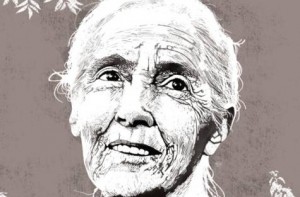

By Nadia Eldemerdash

The renowned primatologist’s undying love for chimpanzees meant she was destined to work with the animals

Not everyone’s adult career turns out as they would have hoped in their childhood. But a young Jane Goodall would approve of the work of her older self.

As a child, Goodall’s father gave her a toy chimpanzee named Jubilee, after a chimp in the London Zoo, sparking her initial love for and interest in animals. Her favourite books were Tarzan and Dr Dolittle — a 2006 book by Brad Dunn quotes her as saying “I wanted to talk to the animals like Dr Dolittle.”

The adult Jane still keeps that toy chimpanzee. It is symbolic not only of a childhood dream come true, but of her ground-breaking work as the only human to be accepted into a chimpanzee troop.

Her discoveries about chimpanzee behaviour in the 1960s were startling to the scientific community. Goodall was the first to record that chimpanzees were not vegetarians, hunting and eating the smaller colobus monkeys. She also discovered that they could make and use tools to eat termites and carry water. The idea that animals other than humans could build and use tools was unheard of at the time. In fact, her mentor Louis Leakey wrote that her discovery would force scientists to “redefine man, redefine tool, or accept chimpanzees as human”.

“Chimpanzees, more than any other living creature, have helped us to understand that there is no sharp line between humans and the rest of the animal kingdom,” Goodall said in a 2007 TEDGlobal talk. “It’s a very blurry line, and it’s getting more blurry all the time.”

Goodall was one of the first researchers to blur this line. Arriving at the Gombe Stream National Park in Tanzania in 1960 with no college research background, the findings she made were very different from those made by the by-the-numbers approach of other scientists.

“You can imagine my dismay when I got to Cambridge and found that I had done everything wrong. I shouldn’t have named the chimps; I should have given them numbers,” Goodall told CNN in a 2005 documentary. “I couldn’t talk about their personalities, their minds or their feelings because that was unique to us.”

But it is exactly what she couldn’t talk about that was most revolutionary in our current understanding of chimpanzees and other primates. Today, it is widely accepted, that chimpanzees, like humans, have individual personalities and specific dynamics that govern their relationships with members of their troop.

Darker side

That they are capable, like humans, of love and compassion, but also of cruelty and aggression, was something Goodall herself had not anticipated.

Goodall observed that dominant mothers would sometimes kill and even eat the babies of lesser-ranking females, and that in turf wars between rival chimpanzee troops, males would mercilessly beat their opponents and leave them to die of their wounds. In her 1999 book Reason for Hope: A Spiritual Journey, she writes “I had believed … that the Gombe chimpanzees were, for the most part, rather nicer than human beings … Then suddenly we found that chimpanzees could be brutal — that they, like us, had a darker side to their nature.”

Her unconventional, unobjective approach was what eventually endeared her to a high-ranking troop male, whom she named David Greybeard for the tuft of grey hair on his chin, to accept her into his troop. For 22 months Goodall was the lowest ranking member, during which she got an up-close and personal look into the behaviours and dynamics of the chimpanzees. She was forced out of the troop by a new alpha male, Frodo, who had frequently attacked her.

In 1977, Goodall established the Jane Goodall Institute, which continues to support research at Gombe and acts as an advocate for primates and their habitats. The institute also has a youth arm, Roots and Shoots, which supports youth-led campaigns focused on conservation and the environment.

Goodall told CNN: “My mission is to create a world where we can live in harmony with nature. And can I do that alone? No. So there is a whole army of youth that can do it. So I suppose my mission is to reach as many of those young people as I can through my own efforts.”

When she began her research, Goodall had only her experience working as a secretary. She went on to earn a PhD in 1965 from Cambridge University, becoming one of only eight people allowed to study for a doctorate without getting an undergraduate degree.

She has earned 30 awards and honours since 1980, almost one every year. She was made a Commander of the Order of the British Empire and received a National Geographic Society Hubbard Medal in 1995, and in 2002 she was made a United Nations Messenger of Peace. She has written almost two dozen books for both adults and children and appeared in numerous films and documentaries about her work.

Now 79, Goodall remains active and is heavily invested in her advocacy work for chimpanzees, spending her time speaking, as she puts it, “for the hundreds of chimpanzees who … cannot speak for themselves,” and raising money for JGI.

“The long hours spent with [chimpanzees] in the forest have enriched my life beyond measure,” Goodall says in a 2009 paper on her work and activism by Connie Jankowski. “What I have learnt from them has shaped my understanding of human behaviour, of our place in nature.”

Source: GulfNews.com. No Trademark infringement is intended.